Museums In Gozo

Exploring Gozo’s Rich Heritage: Must-Visit Museums On The Island Of Gozo

Ġgantija, meaning ‘place of the giants’ is the oldest and one of the best-preserved megalithic complexes in Malta. Its name comes from the legend that it was built by a giantess, a story that acknowledges the huge dimensions of the Ġgantija temples that make up this UNESCO World Heritage Site in Xagħra, Gozo.

Similar legends have also given their names to other megalithic structures across Europe such as the ‘Tomba dei Giganti’ in Sardina, ‘Hunebedden’ in the Netherlands and the ‘Barclodiad y Gawres’ in Wales. Giants have been a part of mythology, folklore and religion for thousands of years and it’s only logical that they’ve weaved their way into the megalithic era, a time when humungous stones were being quarried, carved and erected long before sophisticated engineering techniques had been developed.

The south temple at Ġgantija temples dates back to around 3600 BCE is the oldest of the two and consists of five apses with parts of its outer wall still stretching to a gargantuan height of six metres. The north temple was built later and has a terminal niche instead of a full apse at its rear. Both entrances face southeast, a direction that is common for nearly all the Maltese temples, the main exception being Tal-Qadi near Naxxar which was oriented to the northeast. Iron Age roundhouses in England often faced the south-east, as did many later Roman villas and it’s thought this was for the practical purpose of attracting the most sunlight and warmth. Although, there’s the obvious possibility that astronomical alignments played a role, whether for agricultural planning or for ceremony and religion.

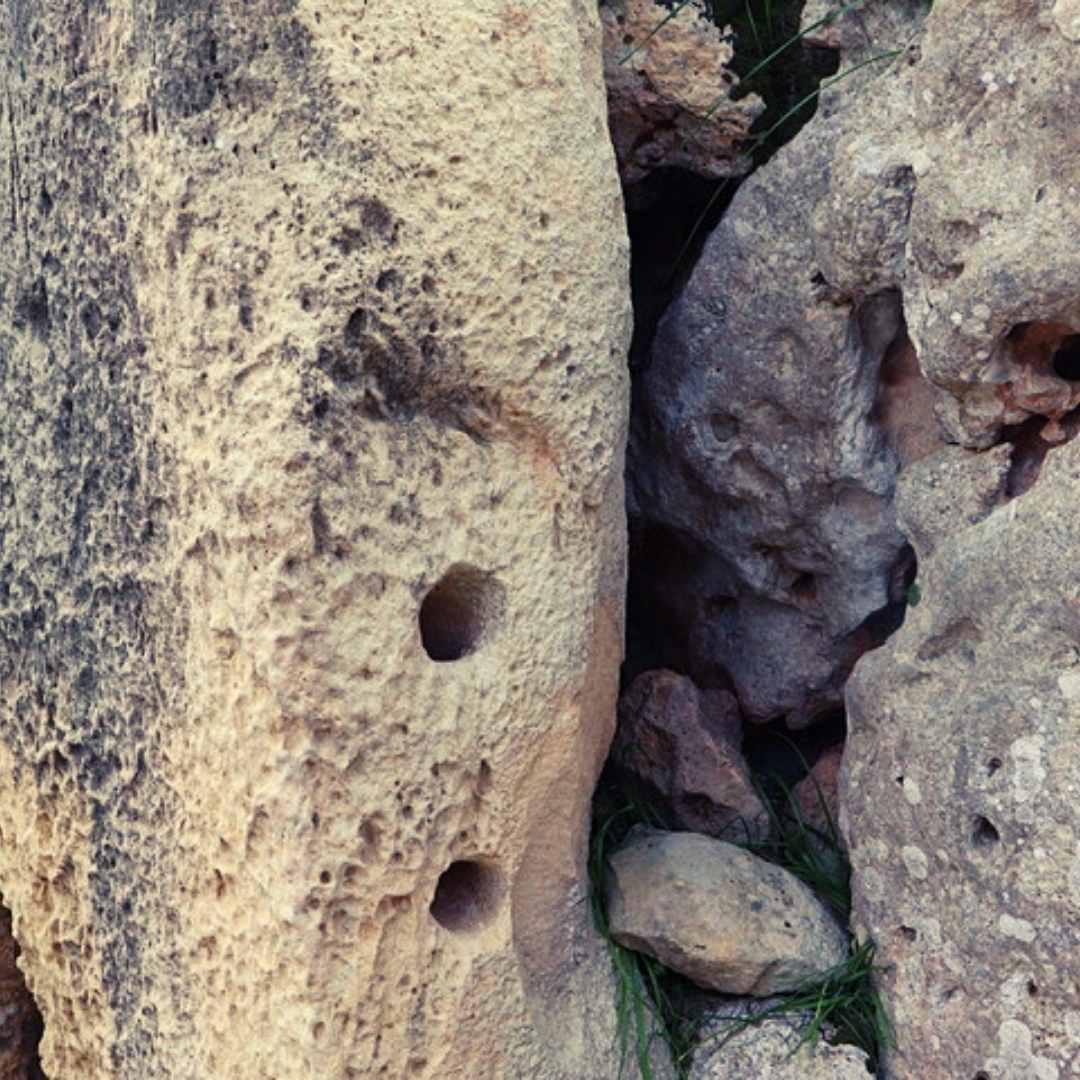

Incredible finds have been excavated from the Ġgantija temples ever since antiquarians first paid attention to them in the 18th century. There are altar-type structures in several apses, a hearth which still shows evidence of burning, pottery, ‘fat lady’ statues, animal bones, wall plaster painted with red ochre and a conical-shaped menhir or standing stone. Holes cut into the stone blocks on either side of entrances leading to different parts of the temples were probably some sort of ancient hinge for attaching a door made of a material that has long since decomposed. All the finds point to ritualistic activities but the exact nature of these is still elusive.

Underneath a threshold stone at the entrance to the south Ġgantija temple, various pottery sherds were excavated along with a bowl containing 158 seashells and the horn of a bull. These appear to have been ritual deposits made when the temple was founded, probably to confer good luck on its construction or on the future of the building. Strangely, for an island-dwelling population, the temple people didn’t eat seafood (Malone et al. 2020, 304) but seashells seem to have been used as jewellery and in burials which adds weight to the idea that the threshold deposit was of symbolic importance. Stone spheres lying around the outer wall have been found at other temples as well and it’s thought they were used as rollers to move the huge megalithic blocks into position. But, once again, this is not conclusive.

Cavities cut into the floor of the Ġgantija temples have often been referred to as ‘libation holes’ due to the theory that ritual offerings were poured into them on arrival at the temple complex. In the Temple Places monograph related to the FRAGSUS Project which took place between 2013 and 2018, it’s speculated that these holes could have been for wooden stakes with animal skulls on top, placed at the entrances as part of a ritual feasting ceremony (Malone et al., 2020, 288). The FRAGSUS Project also revealed a spring and fault line at Ġgantija (Malone et al., 2020, 18-20) which offers up the intriguing possibility that these landscape features were important to the temple people when choosing locations for construction.

At the moment the Ġgantija temples are approached from the visitor centre in the northwest but watercolours and engravings from the 19th and 20th centuries show a trilithon entrance in the south of the man-made megalithic terrace. This would mean the ancients accessed the complex by walking up a slope, possibly in a ceremonial procession. The FRAGUS Project discovered megalithic blocks which may have been a part of this original trilithon (Malone et al., 2020, 169-191), as well as the remains of a ramp. They both date to the Tarxien phase so would have been in use later than when the first temple was built. These megalithic blocks can still be seen, built into the rubble wall that forms the southwest of the terrace.

Just a casual glance in the direction of Ġgantija shows how accomplished the ancient temple people were.

Stepping into the visitor centre at the Ġgantija temples and walking around the megaliths makes it all the more clearer that the Neolithic people were complex and cultured. But so many questions remain. Where did they come from and where did they go? What rituals did they practice and which deities did they worship? How significant were the cosmos to their everyday life? Why didn’t they eat seafood? Why did they go to such efforts to move blocks of limestone weighing tonnes? How were the different megalithic sites related to each other? Did the fat lady statues represent goddesses, priestesses, or neither? Ġgantija is not just an incredible megalithic complex, it’s a monument to an enduring mystery.

References Malone, C., Grima R., McLaughlin, R., Parkinson, E. W., Stoddart, S., & Vella, N., 2020.Temple Places: Excavating cultural sustainability in prehistoric Malta. (FRAGSUS: Fragility and Sustainability in the Restricted Island Environments of Malta Volume 2). Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Intrigued to learn more about this mind-boggling era? Check out the MegalithHunter’s Website, Instagram, and Facebook

Author and Images: Laura Tabone Editor: GITH

Meet Laura Tabone. After years in business, Laura pursued her passion and fascination with the megalith builders of the Neolithic and undertook a Master of Arts in Mediterranean Studies from the University of Malta. She is now an independent, lay researcher and takes as much information as she can from academic papers to explore, debate, and try to shed light on the mysteries of prehistoric times. Laura’s dream is to find undiscovered megaliths while exploring the globe as the MegalithHunter.

Exploring Gozo’s Rich Heritage: Must-Visit Museums On The Island Of Gozo

Tal-Mixta Cave Is A Must-Visit When On Holiday In Gozo.

Fresh Finds Gozo Mercato is a curated makers market in Gozo, Malta and the second edition is this March.